Over half the named species of tree-kangaroos in existence today

occur in the high montane forests of New Guinea. These all fall in the

category of the highly-derived species and some are reported to be quite

specialised in diet and behaviour (Martin, 2005). New Guinea's highlands are

very young, with most tectonic uplift occurring over the last 5 million years,

with evidence that uplift is still happening (Riker-Coleman et al, 2006).

Ancestral tree-kangaroos would have

happily moved into these lush, well-forested mountain tops and from there, just

like Petrogale species isolated

on rocky outcrops, speciated. It may be that this speciation occurred

purely as a result of long isolation by time: it's quite a long way from one

mountain-top to another, but equally likely is vicariance brought about by

periods of glaciation in the Pleistocene. These glacial periods are well-known

to have affected the distribution of vertebrates in Australia's Wet Tropics

(Winter, 1997).

Palynology tells us that over the past

190,000 years, the rainforests of the area have undergone repeated expansions

and contractions and that as a result, mammal distributions have become

determined by the persistence of refugia (Winter, 1997). In the Wet

Tropics region, for example, mammal distribution can be divided into two

discrete refugia: the Thornton Unit to the North and the Atherton unit to the

south, divided by an 80km wide gap of dry forest known as the Black Mountain

Corridor (Bell et al, 1987). It is thought that mammals were confined to

either one or the other of these two refugia and a subsequent warm and wet vicariant

phase determined the distribution of cool-adapted upland isolate species

(Winter, 1997). While isolation into

these refugia has not been cited as a determining factor for tree-kangaroo

distribution in the Wet Tropics, it is interesting that the ranges of Australia’s

two species do fall generally into one of these two units. It is therefore not entirely unlikely that the same basic pressures that cause speciation in many organisms, i.e. geographic and reproductive isolation brought about by vicariance, have been the cause of the diversity of tree-kangaroo species in existence today.

|

| Figure 1. Wet Tropics region showing the Black Mountain Corridor (black bar). Source: Taberlet, 1998 |

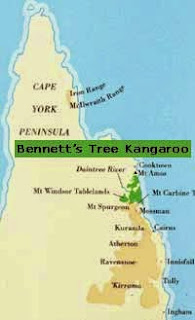

Figure 2. Comparative distribution maps of the two Australian species of tree-kangaroo. Source: www.tenkile.com Accessed 22/5/15

Bell, F. C. (1987, May). Distribution, area and tenure of rainforest in northeastern Australia. Royal Society of Queensland.

Martin, R. (2005). Tree-kangaroos of Australia and New Guinea. CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne.

Riker‐Coleman, K. E., Gallup, C. D., Wallace, L. M., Webster, J. M., Cheng, H., & Edwards, R. L. (2006). Evidence of Holocene uplift in east New Britain, Papua New Guinea. Geophysical research letters, 33(18).

Taberlet, P. (1998). Biodiversity at the intraspecific level: the comparative phylogeographic approach. Journal of Biotechnology, 64(1), 91-100.

Winter, J. W. (1997). Responses of non-volant mammals to late Quaternary climatic changes in the wet tropics region of north-eastern Australia. Wildlife Research, 24(5), 493-511.